Sex workers driven further to the margins by the coronavirus crisis

Sex work is a centuries-old global occupation, yet sex workers have always been marginalized. The sector has historically (Truong, 2015) been regulated to keep tabs on the social, racial, political and economic engagement of its workers. The regulation of the activities and bodies of sex workers worldwide, and their marginalization are predominantly a colonial legacy (Irwin, 1996). In the contemporary age, sex work is approached in binaries, seen either as legal (but regulated) labour or conflated with sex trafficking, which encourages its illegalization.

Concerning the radical changes enacted worldwide due to the spread of the coronavirus, including lockdowns and the temporary halting of high-risk occupations, it appears that the livelihoods, financial security and health situation of sex workers are at risk (PTI, 2020). Some sex workers have used social media platforms to point to the decline in the number of clients and income, and to increasing health risks following the outbreak of Covid-19. For instance, one sex worker used a chain of threads and tweeted that,

There’s no clients! Nobody in their right mind is having sex with a stranger during a pandemic. So often we’re not even given the option of seeing clients! Which means we’re BROKE. (Caradonna, 2020)

Some sex workers are even offering extra unpaid services to continue drawing clients during the crisis. For instance, a number of sex workers are offering services such as ‘pay for 12 hours and get 12 free’. Indeed, sex workers in the global South, in India (PTI, 2020) for example, are struggling to make temporary arrangements to make ends meet, even fearing possible starvation if the current crisis endures. This explicitly speaks to the severity of the coronavirus crisis and the strategies for survival employed by sex workers themselves. Some civil society and volunteer groups have come forward to help people in sex work areas and are providing them with essential food packets. Sex workers’ communities and collectives have also come forward to raise funds to support sex workers (SWARM, 2020) who are suffering from financial stress during this coronavirus pandemic. But is it sex worker’s responsibility to ensure their survival? What role should the state play in helping sex workers stay afloat financially?

Some sex workers are even offering extra unpaid services to continue drawing clients during the crisis. For instance, a number of sex workers are offering services such as ‘pay for 12 hours and get 12 free’. Indeed, sex workers in the global South, in India (PTI, 2020) for example, are struggling to make temporary arrangements to make ends meet, even fearing possible starvation if the current crisis endures. This explicitly speaks to the severity of the coronavirus crisis and the strategies for survival employed by sex workers themselves. Some civil society and volunteer groups have come forward to help people in sex work areas and are providing them with essential food packets. Sex workers’ communities and collectives have also come forward to raise funds to support sex workers (SWARM, 2020) who are suffering from financial stress during this coronavirus pandemic. But is it sex worker’s responsibility to ensure their survival? What role should the state play in helping sex workers stay afloat financially?

The precarity of sex work

Policy makers and feminists have different approaches (Doezema, 2002) to sex work. Some view it as a form of ‘exploitation’, while others see it as a form of work, framed in relation to individuals’ agency. The contestation is further complicated by the global anti-trafficking discourse, which largely conflates sex work with sex trafficking and encourages the criminalization of sex work. The United Nations Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children (UN TIP Protocol, 2000) clearly promotes such a criminalization framework, which, after acknowledgement by the majority of nation-states, is shown to have a strong negative impact (Kempadoo, 2015) on the lives and livelihoods of sex workers. Indeed, within such a dominant frame, institutional support largely reaches sex workers when they represent themselves as victims of trafficking rather than as independent agential sex workers. My personal field of engagement in India’s largest red-light district in Sonagachi has provided ample evidence that the criminalization framework encourages the incarceration of sex workers who resist being framed as victims of trafficking and the dismissal of their basic human rights.

…a number of sex workers are offering services such as ‘pay for 12 hours and get 12 free’.

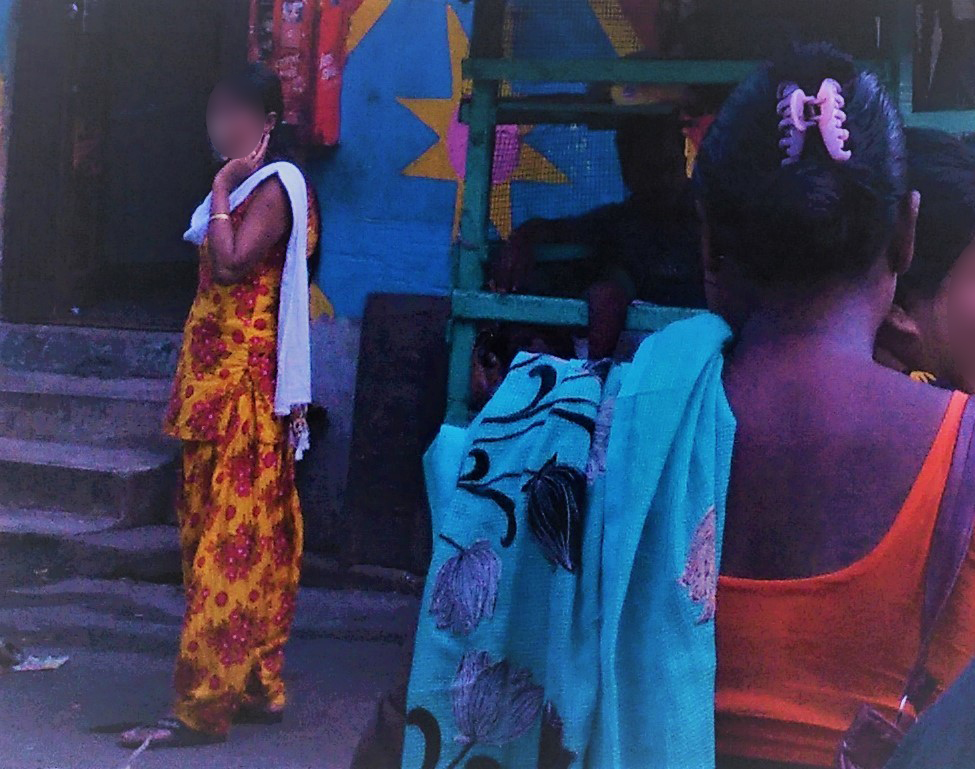

The tensions are also embedded in an intersectional system that supresses sex workers socially, politically, economically and as individuals. During interviews conducted as part of my ongoing fieldwork on the research topic ‘Locating marginalized voices in human trafficking discourse: learning from the experiences of urban subalterns in India’ in Asia’s biggest red light district in Sonagachi, Kolkata, sex workers often noted the issue of exclusion from or discrimination in public healthcare services and in trying to access welfare benefits due to their occupation. Moreover, a majority of sex workers are working with concealed identities and are using surrogate jobs titles to deal with social stigma and tensions in the family. Such tensions indicate elements of hardship already existing in the worker’s lives.

The current coronavirus pandemic creates a further situation of hardship for them as they avoid working in streets and brothels and lose a share of income, which they present to their families as a salary from surrogate jobs, in addition to their crucial need to earn money to support themselves and their families. From my recent telephone conversations with sex workers in India, after the outbreak of coronavirus pandemic, it appears that some sex workers are migrating back to their native villages as they cannot afford the expenses and possible risks in Sonagachi. Besides, it appears that the situation has become riskier and harsher for those migrant sex workers who stay back or who even cannot go back to their native villages, especially undocumented migrant sex workers from outside states and outside national boundaries. The situation of trans-sex workers is even harsher as they are largely unsupported by societal institutions like family and have been excluded or thrown out from their homes or villages due to their sexual identity. Such workers do not even have the option to go home during this crisis situation. This highlights the view that the state’s institutional support during such crisis situations is essential.

The current coronavirus pandemic creates a further situation of hardship for them as they avoid working in streets and brothels and lose a share of income, which they present to their families as a salary from surrogate jobs, in addition to their crucial need to earn money to support themselves and their families. From my recent telephone conversations with sex workers in India, after the outbreak of coronavirus pandemic, it appears that some sex workers are migrating back to their native villages as they cannot afford the expenses and possible risks in Sonagachi. Besides, it appears that the situation has become riskier and harsher for those migrant sex workers who stay back or who even cannot go back to their native villages, especially undocumented migrant sex workers from outside states and outside national boundaries. The situation of trans-sex workers is even harsher as they are largely unsupported by societal institutions like family and have been excluded or thrown out from their homes or villages due to their sexual identity. Such workers do not even have the option to go home during this crisis situation. This highlights the view that the state’s institutional support during such crisis situations is essential.

State support essentially needed

In pandemic situations, states generally come forward to support those who are suffering from a loss of income (for example, see how the United States is responding in Cook, 2020). But due to the illegality or precarity of the occupation in many contexts, sex workers are often not seen as entrepreneurs who qualify for government subsidies or financial assistance. In such cases, there would be no mandate or institutional responsibility to offer financial packages, healthcare services or relief benefits to sex workers. Industries and several unorganized work sectors suffering losses due to the coronavirus pandemic have been offered financial packages or healthcare benefits by several government agencies or employing institutions. But if sex work is not a commercially acknowledged industry, sex workers will be further cornered and will suffer further marginalization.

…sex workers often [face]… exclusion from or discrimination in public healthcare services and in trying to access welfare benefits due to their occupation.

Also, being a non-acknowledged industry, sex workers have no way of benefitting from other government support systems that have made several provisions to protect employees and companies alike. Indeed, those states that regulate sex work as work have imposed a recent ban (Pieters, 2020) on the commercial activities related to this type of work due to the coronavirus pandemic. This will potentially encourage financial instabilities and further precarities among sex workers if no institutional support is provided (Schaps, 2020).

The system of non-acknowledgement of sex work in established policies therefore excludes sex workers from entitlements or rights and essentially hides sex workers during a pandemic situation, as the current coronavirus pandemic has demonstrated. It also holds back the political, social and institutional responsibility of the state and other actors, including civil society, towards marginalized communities of sex workers. The onus, in contrast, is indeed forcefully and irresponsibly imposed on sex workers to manage their situation, survive and take high risks for the fulfilment of their basic human needs. Changes in the global socio-political landscape due to the coronavirus pandemic are hence leading to further burdens and precarities (Hobbes, 2020) in the lives of sex workers, whereas the institutional system is failing to show any sign of support. But it is also a learning opportunity for sex workers’ collectives and their allies in preparing responses to future pandemic situations. Last but not least, and importantly, the crisis also puts in the spotlight the desirability of the criminalization approach toward sex work that exists in dominant anti-trafficking models.

References

Caradonna, L. (2020) Tweet 11 March 2020. https://twitter.com/LydiaCaradonna/status/1237752816678121480

Doezema, J. (2020) ‘Who Gets to Choose? Coercion, Consent, and the UN Trafficking Protocol’ Gender and Development Vol. 10, No. 1.

Hobbes, M. (2020) ‘Coronavirus Fears Are Decimating The Sex Industry’, Huffington Post, 12 March 2020. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/seattle-sex-workers-covid19-coronavirus_n...

Irwin, M. A. (1996) ‘”While Slavery” as Metaphor Anatomy of a Moral Panic’, https://walnet.org/csis/papers/irwin-wslavery.html

Kempadoo K., Sanghera J., Pattanaik, B. (2015) Trafficking and Prostitution Reconsidered:New Perspectives on Migration, Sex Work, and Human Rights, New York: Routledge.

PTI (2020) ‘Sex workers face uncertain future in COVID-19 time’. Outlook news scroll, 27 March 2020. https://www.outlookindia.com/newsscroll/sex-workers-face-uncertain-futur...

Cook, N. (2020) ‘Trump pledges financial help to counter coronavirus losses’ Politico, 9 March 2020. https://www.politico.com/news/2020/03/09/donald-trump-fiscal-stimulus-me...

Pieters , J (2020) ‘MANY SEX WORKERS IGNORING CORONAVIRUS DISTANCING MEASURES: REPORT’. NLTIMES.NL, April 1, 2020 https://nltimes.nl/2020/04/01/many-sex-workers-ignoring-coronavirus-dist...

Swaps, K. (2020) ‘Dutch sex workers risk trafficking and abuse as coronavirus bites’, Reuters, 20 March 2020. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-netherlands-sexwor...

SWARM (2020) Tweet 13 March 2020. https://twitter.com/SexWorkHive/status/1238467356923494400

Truong, T-D (2015) ‘Human Trafficking, Globalisation and Transnational Feminist Responses’, Working Paper no. 579 p. 1- 35, The Hague: Institute of Social Studies.

UN TIP Protocol (2000) ‘Protocol to Prevent, Supress, and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, supplementing the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime’.

PhD researcher at ISS

…being a non-acknowledged industry, sex workers have no way of benefitting from other government support systems…

All photographs were taken by the author at Sonagachi, Kolkata. India’s largest red-light district.

Share

Check our website for latest news, upcoming events, recent PhD defences, and the ISS library for working papers, PhD theses and the journal Development and Change.

Check our website for latest news, upcoming events, recent PhD defences, and the ISS library for working papers, PhD theses and the journal Development and Change.